A little dissidence

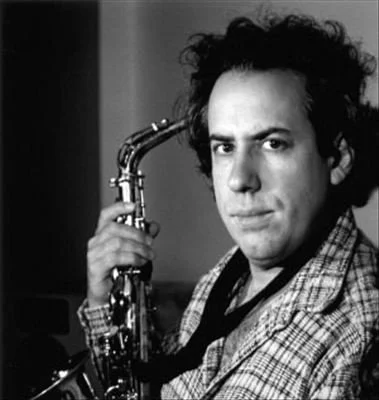

Jean Derome

rOLE in Michka’s FILMS

The Sleeping Tree Dreams of its Roots — Original music

The Snail Position — Original music

Jean Derome

JD: I think I knew Michka through Robert Daudelin, who was director of the Cinématèque québécoise. Robert was active in Montreal jazz scene, and Michka — his partner at the time — also loved music, and had a good ear. Musicians always recognize these people, those for whom music is not just “background” but has an important presence in their lives. A musician develops friendships with people like that.

Robert Daudelin was directing a documentary about the saxophonist Lee Konitz. One night when Konitz was in Montreal, Robert and Michka invited me, and several other several other jazz fanatics, for dinner at their house. They were filming the dinner as part of the film. Michka had cooked a lamb couscous, and it was really delicious. It really struck me, her talent for cooking.

After that, I met up with Michka quite often. She knew our trio DGT – Derome Guilbeault Tanguay — and often came to hear us play in the jazz clubs. After we did the score for The Sleeping Tree Dreams of its Roots, we always talked about new projects. With The Snail Position, she really gave us carte blanche. We approached it a little like the music of Miles Davis for the Louis Malle film Elevator to the Gallows.

Normally, when you compose music, in addition to the length, you decide the tempos and the number of bars for each sequence in advance. That's really the starting point. Then you develop and try out themes. Usually you’re very prepared by the time you reach the studio. But for The Snail Position, Michka was willing to try something different. I was touched by her trust in us. With the Trio DGT, we tried something spontaneous. I had absolutely no music composed in advance, and we recorded all of it in the order it appeared in the film. I would show the sequence to the musicians, and we would do about three takes for each one. It was really engaging because from one take to the next, there was a lot of variety. After we'd recorded everything, we'd choose our favourites.

No one ever noticed that everyone we see walking in this film is accompanied by music that captures their rhythm. It’s a technique you often see in cartoons, but I had never seen that in a fiction film, and, thankfully, it didn’t have a comic effect. We accompanied people — not only in their physical steps, but also in their journey as characters — to create empathy. I wouldn't have tried this with any other group, but Normand Guilbeault, Pierre Tanguay and I had such strong swing that we could it.

There are maybe three different types of music in the film. I used different saxophones, but certain scenes called for the flute, especially the ones attached to childhood memories. The scene in the souk, for example, was played with the ocarina.

It brought me such joy to see Michka so content, and to receive her feedback so spontaneously. She had such confidence in our music, and she had a profound appreciation for what we did.

MF: The song, "Michka", was composed with the flute. Was it done for the film or afterwards as a kind of tribute?

JD: It was a piece I was composing at the same time as Michka hired me for the film. I was very fond of Michka. There was a tenderness and charm in this piece that reminded me of her.

I gave her a whole stable of “mood” pieces that she could use when music was playing in “real life”, in public or at the house. It was another layer of music that came out of the action in the film. The “Michka” piece may not be dramatically important in the film, but I was happy to bring it to life.

MF: One night Michka and I went to see the Trio at the Upstairs Club in Montreal. When you noticed her, you decided right away to play the piece "Michka". You had to talk to the other band members and change the instrumentation. The memory is precious because it evokes the essence of jazz — this improvisation.

“For The Snail Position, Michka was willing to try something different. I was touched by her trust in us. ”

JD: I don’t have a lot of music in my repertoire that is named after someone. So to honour Michka in that way gave me a lot of pleasure.

MF: When you wrote the music for The Sleeping Tree, did you use a different method or something similar?

JD: Most of the pieces were composed in a more conventional way. But I remember one shot where an Asian man is walking down a hill in the snow accompanied by Pierre Tanguay on darbouka. Suddenly, the man slips, and we improvised with Pierre capturing the man’s movements through music. That really opened the door for the music for The Snail Position because we realized the approach was lively and interesting. But above all Michka was open to it. A composer can be convinced a musical idea is excellent, but if the filmmaker doesn't like it, it's a failure.

It takes heart-to-heart meetings with a filmmaker to understand as much as possible what she wants for her film. It's good to know their musical tastes too because sometimes filmmakers can’t find the words to describe what they want. It’s difficult to talk about music.

Sometimes, I feel like a tailor. I need to create clothes that someone will be proud to wear for a long time. In the case of Michka, we had the same musical references so the field was completely open. It was wonderful.

MF: You have to satisfy the filmmaker, but she had always told me how important it is to give her team the space to be artists themselves. Even though she knew she would never use a “beauty shot” from her cinematographer, for example, she gave him the freedom to take it.

JD: Well, that's it. When someone gives you free rein, you feel like giving even more. And freedom comes with responsibility. You have to ask yourself what you really want to play.

MF: I think there is also the question of respect. She talked to me about that especially in the context of her first film, Far from where? and then her film about American jazzmen, A Great Day in Paris. Instead of taking bits and pieces of music to add colour, she wanted us to hear a whole piece. So Far from where?, for example, was built completely around the song "Ishmael" by Abdullah Ibrahim. In A Great Day in Paris, we hear five or six minutes of music at a time, not just 30 second clips.

JD: These kinds of films are precious to me as a musician. They’re not simply playing background music and transitions. You take the time to listen, to “live” the music.

“Michka must have felt she had more to gain from encouraging a little dissidence and questioning. It’s edgier, and more dynamic. It creates fertile ground for new ideas to germinate. ”

“We had the same musical references so the field was completely open.”

MF: You made The Sleeping Tree in 1991. Had you ever done soundtracks for films before?

JD: I am out of fashion now, but when I was younger I did a lot of them. I must have started doing film music in 1982 or 83. In the beginning, I collaborated frequently with René Lussier. We composed together, which was quite rare. René would do something, and I would write an underlying theme or the other way around. We had a kind of creative ping pong going on. We must have made at least forty films together, mainly documentaries. We also made a lot of animated films, with Pierre Hébert among others.

MF: Michka used to talk about playing ping pong when she was editing. It's still this idea of respect and freedom. She needed someone to push against her ideas.

JD: Yes, exactly, the most interesting creative relationships are a ping pong game where the other person doesn't always have to say "Yes". Otherwise, the results can be horribly conventional and predictable. Michka must have felt she had more to gain from encouraging a little dissidence and questioning. It's edgier, and more dynamic. It creates fertile ground for new ideas to germinate. And I need that. I need to be surprised and challenged.

“She was so sensitive to people who were perhaps a little out of step with society in one way or another.”

MF: You said that you are no longer in fashion for film soundtracks. Michka once told me that you are more respected in Europe than in Quebec.

JD: A lot of jazz musicians, including American musicians, from the 60s on, were treated as artists in Europe but not in the US. A lot of them were surprised to find journalists in Europe who asked serious questions, and that many people were connoisseurs about their music and their recordings. I was performing an avant-garde jazz, musique actuelle, and all that “free” improvised music, and I felt the same way as they did. But now it doesn’t bother me as much.

When I started, it was in 1971, and Quebec nationalism was on the rise. Since I was doing instrumental jazz and improvisation, I didn't work much with words. People said, "That's not Québécois, that's jazz, that's American. It doesn’t have value unless there are lyrics.” It made me angry because sometimes, for example, at the Festival d'été de Québec, they wouldn't hire us, saying, "You're not Québécois.” And yet the program had Mozart. The question didn't even come up for genres like classical. I told them, "There are lots of groups that you call Québécois because they sing in French, but their music is American and not Québécois. It's like Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, but in French.” In Quebec, it always comes back to language. Culture and language became synonymous, and that makes it difficult for painters, sculptures, dancers, musicians...

Innovative Québécois musicians got much more recognition in Europe and in the rest of Canada. People appreciated that we were producing something they had never heard before, and it was exciting — what we called musique actuelle between 1980 and 1985.

It was really striking to us that the acceptance was only coming from outside Quebec. I was very angry with the Montreal International Jazz Festival who never gave us a chance. But, for me, in a sense, this is old news. I don't really care about all that any more.

MF: Do you think it was that very quality — of not being taken seriously in Quebec — that attracted Michka to you? Because she had a nose for it. And she lamented that some of her films, like Prisoners of Beckett, were better received in Europe than in Quebec.

JD: Yes, that could be. In any case, a lot of her films, and a lot of her thinking, was all about recognizing the Other and otherness. She was so sensitive to people who were perhaps a little out of step with society in one way or another. I guess that's another reason why she wasn't afraid to ask us to do the music. She didn't need to compromise. She knew we had chemistry that we could do something dynamic together. Yes, absolutely.

MF: Did you know that she wanted to open a café called “Jazz and Couscous”? She would cook couscous and offer a showcase for jazz. She was sure it would have worked.

JD: What a fabulous idea! I could have tasted her couscous again and played jazz. It would have been so amazing.